Michael Rakowitz: The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one's own (2009)

Michael Rakowitz

the worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own

March 6 - April 4, 2009

Lombard-Freid Projects is pleased to present Michael Rakowitz’s third solo exhibition at the gallery, The worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own. Always surprising and profoundly timely, in this exhibition Rakowitz explores the influence of science fiction genre imagery on the design of Iraqi monuments, military uniforms and weaponry under Saddam Hussein, while illuminating aspects of the US-Iraq conflict over the past few decades. Monumental sculptures that speak through their materials and an accompanying series of narrative drawings come together to tell this most unexpected- yet true- story of the Iraqi leader’s fascination with science fiction. The intertwining forces of adolescent imagination and science fiction, as present in the installation, suggest that the binaries of good and evil found in the mythology developed by innovators such as American director George Lucas are far from categorical when applied to current geopolitical scenarios.

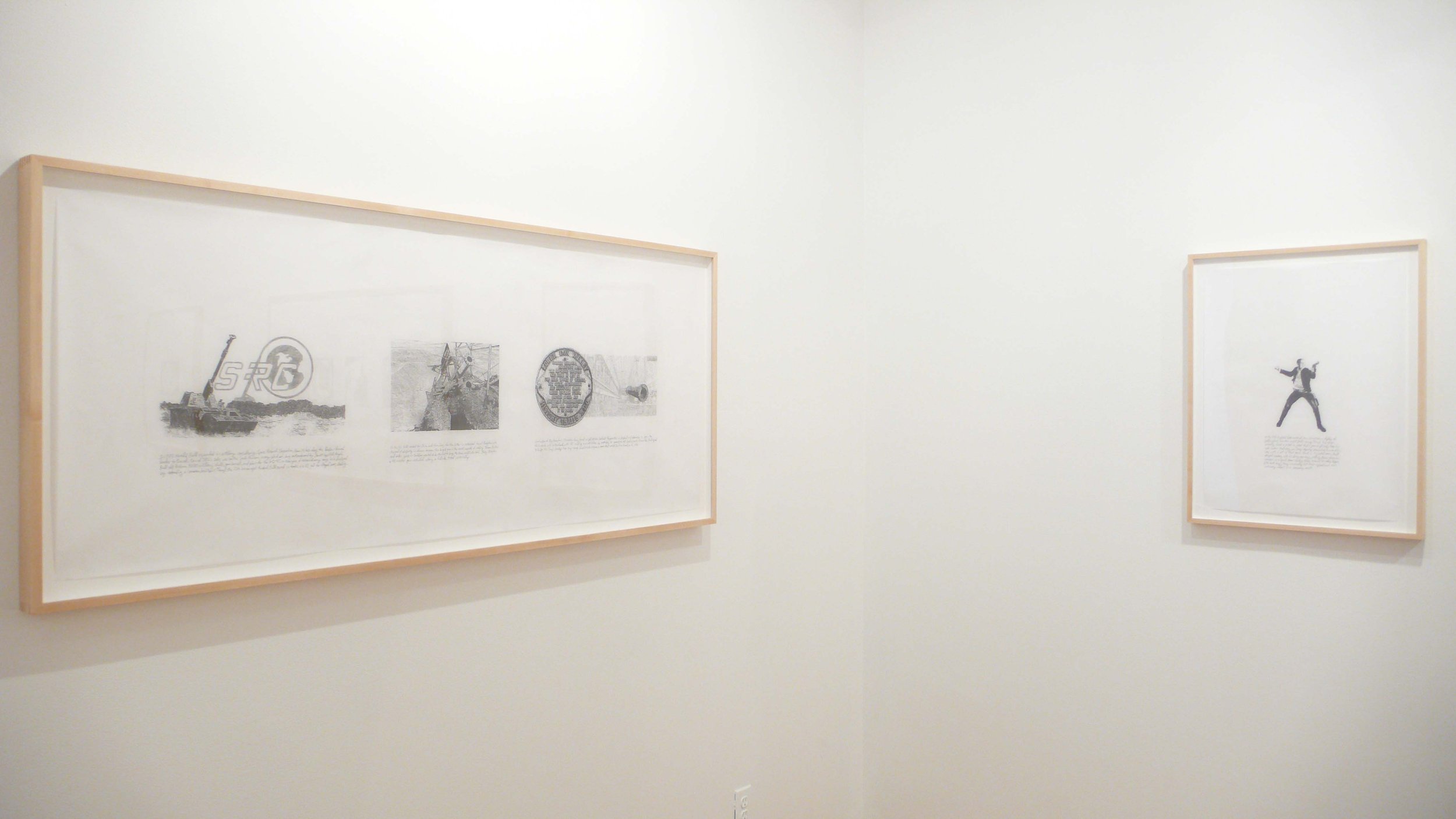

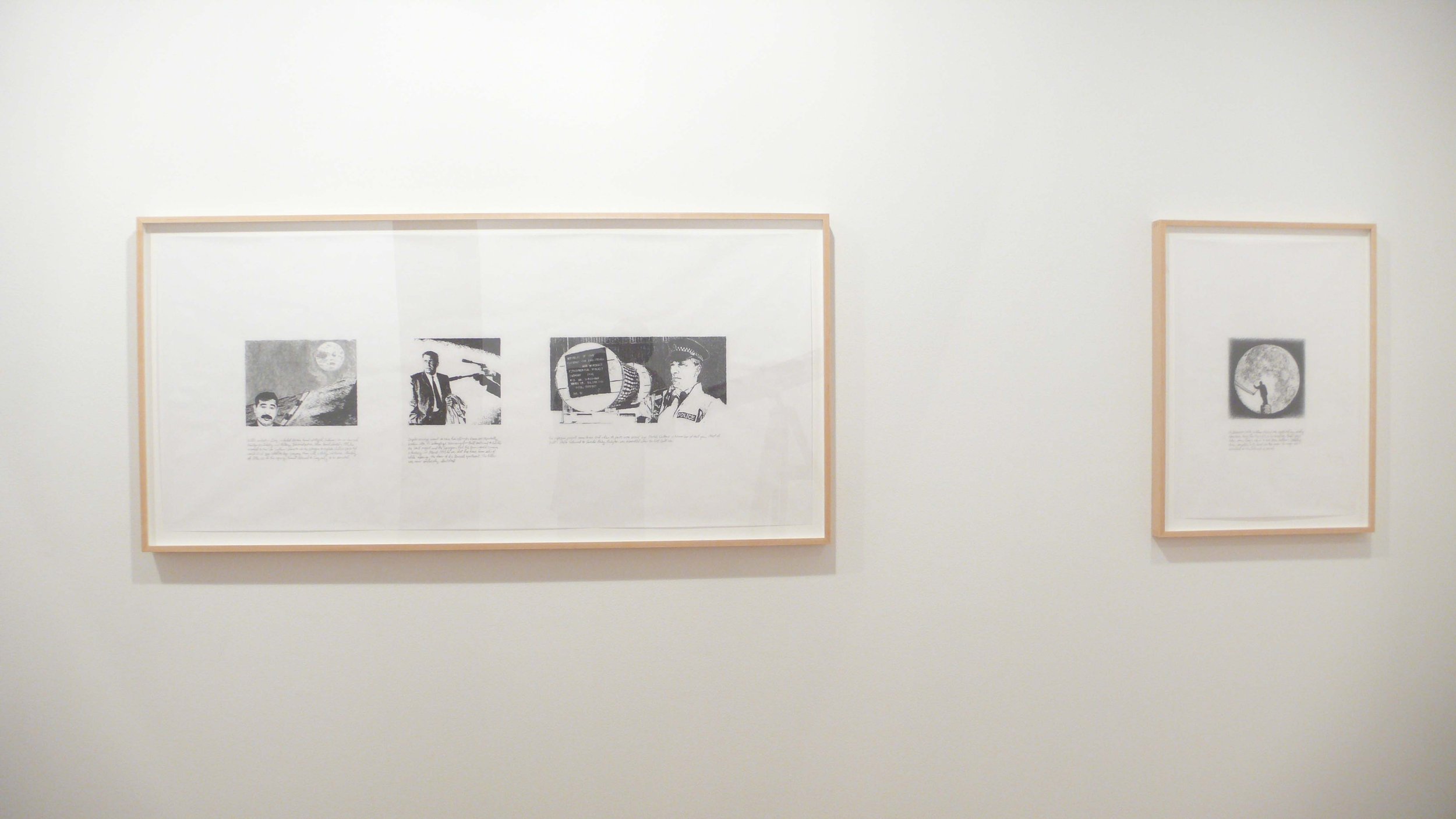

The show title is taken from a speech made by Saddam Hussein in 1985, then reiterated on the invitation card to the inauguration of the Victory Arch, a monument that Hussein built to commemorate the Iraqi victory over Iran in 1989. In 1991, on the eve of the first Gulf War, the Star Wars theme music played as Iraqi soldiers marched underneath the monument for Iraqi TV cameras. Resembling the iconic Star Wars poster in which Darth Vader wields two light sabers, the Victory Arch depicts the hands of Saddam holding two swords, cast from expended Iraqi firearms. In keeping with his conceptual practice of conveying meaning through the recycling of materials, while also a détournement of Saddam's own building principles, Rakowitz has recreated the monument using toy light sabers, whose red and green echoes the Iraqi flag and the Star Wars cosmology of good and evil; papier-mâché from the pages of Saddam's own novels; and deconstructed G.I. Joe figurines, which were introduced in the early 1980s to capitalize on the success of Star Wars action figures and popularize the American military. Helmets in the original monument belonging to fallen Iranian soldiers are represented here by to-scale reproductions of the helmets worn by the paramilitary group formed by Hussein’s eldest son. An avid Star Wars fan himself, Uday Hussein borrowed the exact design of Darth Vader’s helmet to complement the ski-masks and curved swords of his black-clad enforcers responsible for assassinations and intimidation. Ironically, Iraqi government rhetoric after the first Gulf War often articulated the country as having had its sovereignty violated by the US, a “superpower”.

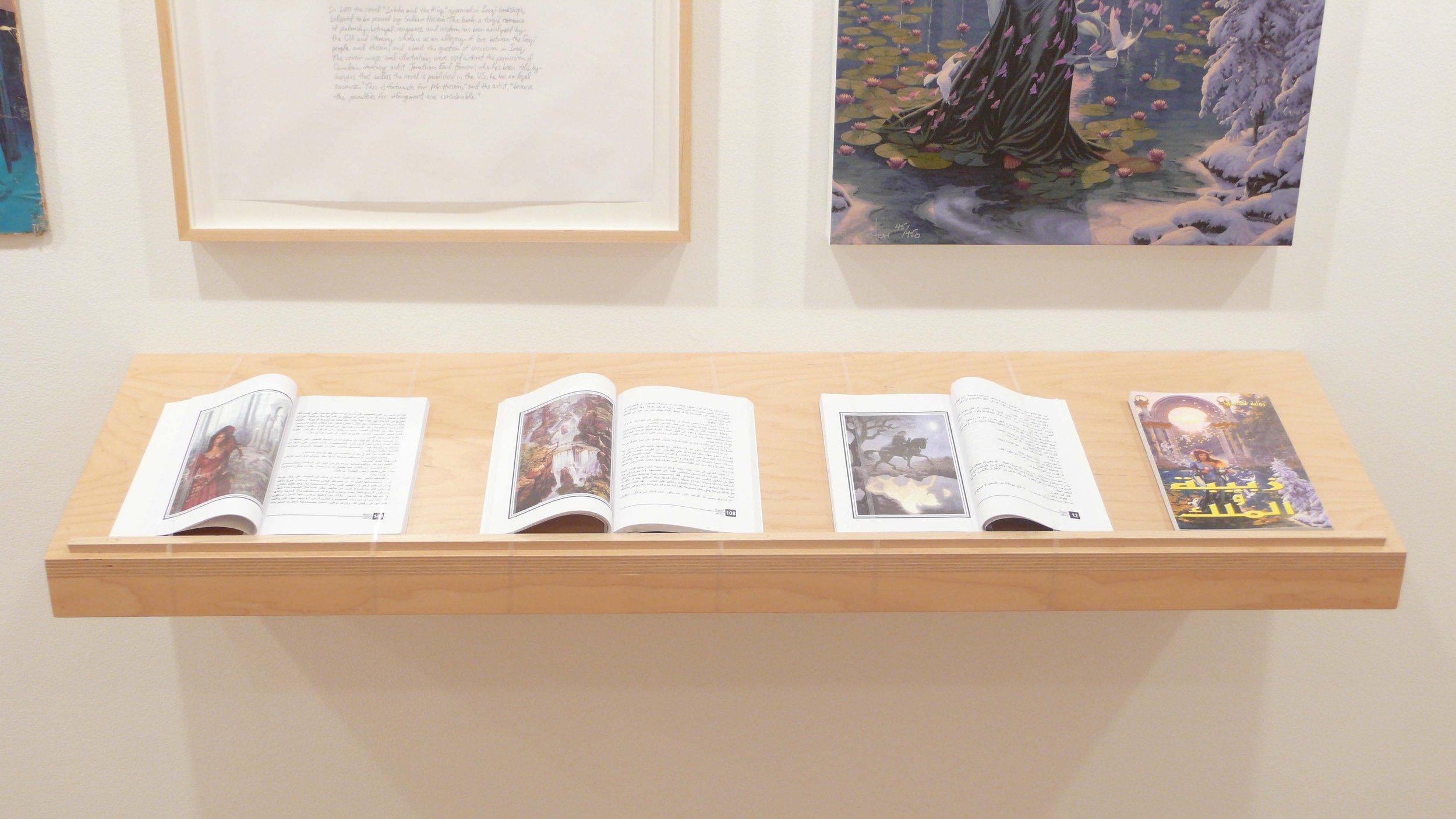

As established in the drawings, Saddam’s fixation with fantasy illustration was far reaching. After Baghdad fell in April 2003, erotic fantasy paintings by Rowena Morrill, a colleague and close friend of the man who designed the famous 1980 Star Wars poster, were discovered by US military personnel in one of Saddam’s mansions. Even more, without permission, Saddam appropriated an image by fantasy illustrator Jonathon Earl Bowser to adorn the cover of his turgid romance novel, Zabiba and the King. An original print of Bowser’s illustration as well as actual copies of the novel will be part of the exhibition. Together with the sculptural elements, the series of drawings unravels the intricacies and complexities of how science turns into science fiction and vice-versa, capturing imaginations and becoming militarized. The drawings depict a young Gerald Bull, the brilliant artillery engineer who went on to work for both the US and Iraqi governments in missile defense development and, after being betrayed by the CIA, developed for the Iraqis a supergun capable of space launches.

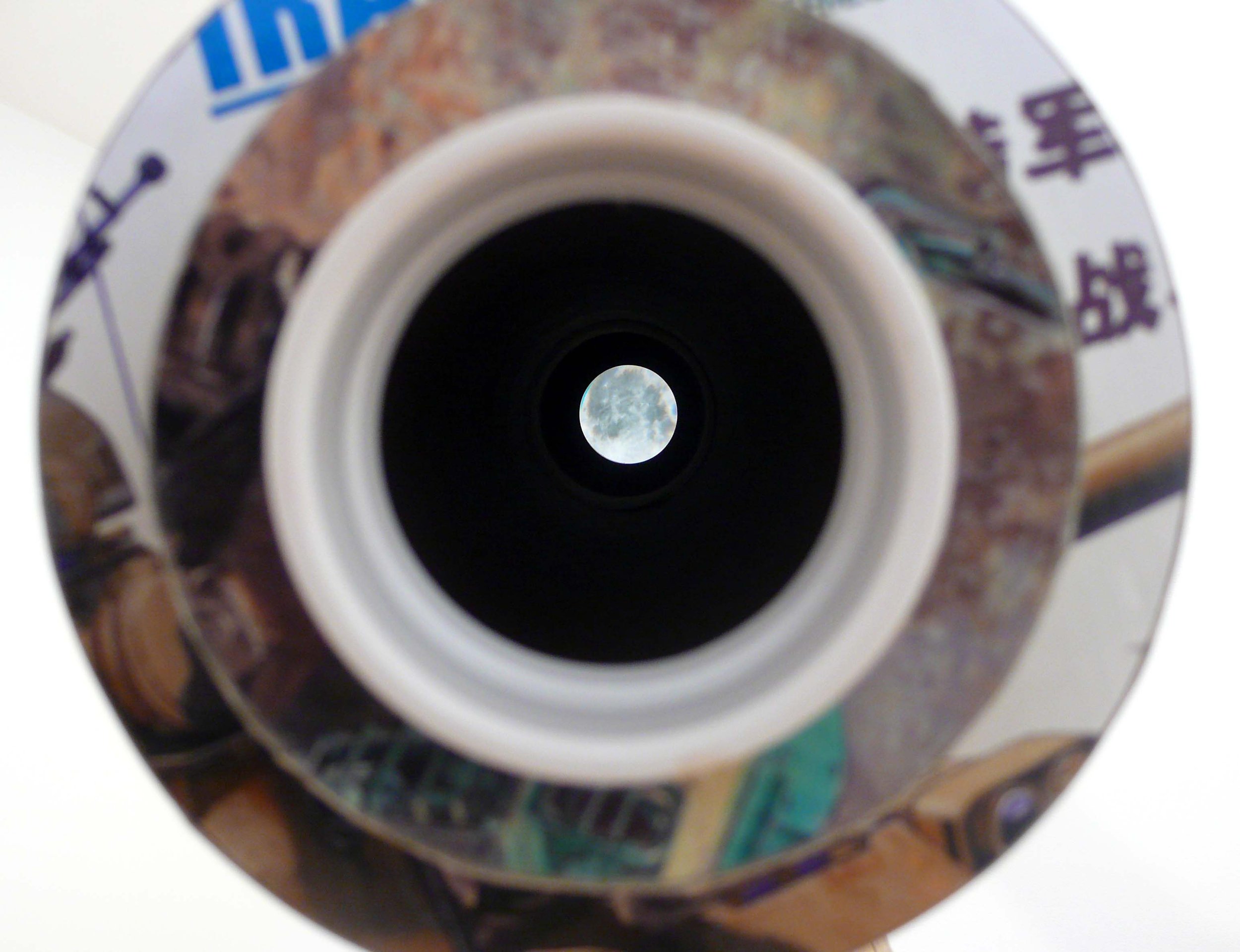

Rakowitz's narrative is conveyed in graphic novel technique and reacquaints viewers with chilling details of the failed Eisenhower-era CIA-authorized assassination of Iraqi leader, Abdul Karim Qasim, by hired gunman, Saddam Hussein. After Qasim’s execution, reports circulated that his face could be seen on the moon, a myth that resurfaced over forty years later on the occasion of Saddam’s execution, as rumors spread that Saddam’s smiling face, complete with beret, was sighted on the moon. In reference to this and modeled after Bull’s efforts, Rakowitz has constructed a telescope “supergun” made from boxes of balsa wood and plastic military models. As Rakowitz weaves the seemingly endless threads of relations, layers of history and fiction interlock and toys are turned into weapons and then back again.

Michael Rakowitz’s recent exhibitions include the16th Biennial of Sydney, Australia; Second Lives: Remixing the Ordinary, Museum of Art & Design, NY; The Greenroom: Reconsidering the Documentary and Contemporary Art, CCS Bard, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY; Heartland, Van Abbemuseum, Netherlands. Upcoming exhibitions include a solo show at the Saidye Bronfman Center of Contemporary Art, Montreal, Canada; Transmission Interrupted, Modern Art Oxford, UK; Return to Function, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Wisconsin.