Mounir Fatmi - Survival Signs

MOUNIR FATMI

SURVIVAL SIGNS

September 7 - October 21, 2017

Jane Lombard Gallery is pleased to present Survival Signs, Mounir Fatmi’s third solo exhibition with the gallery. His work directly addresses the current events in our world and speaks to those whose lives are affected by restrictive political climates. “Survival signs” can also be seen as cultural signs, images, objects, experiences, and their connections and relationships to our everyday life. Is our society fluid, open and accepting, or the opposite? Several of the works in the exhibition teeter along a fine line of interpretation; are they revealing moments of construction or destruction, lightness or darkness? The artist presents his works as signs of survival; elements that allow him to resist and understand the world and its changes.

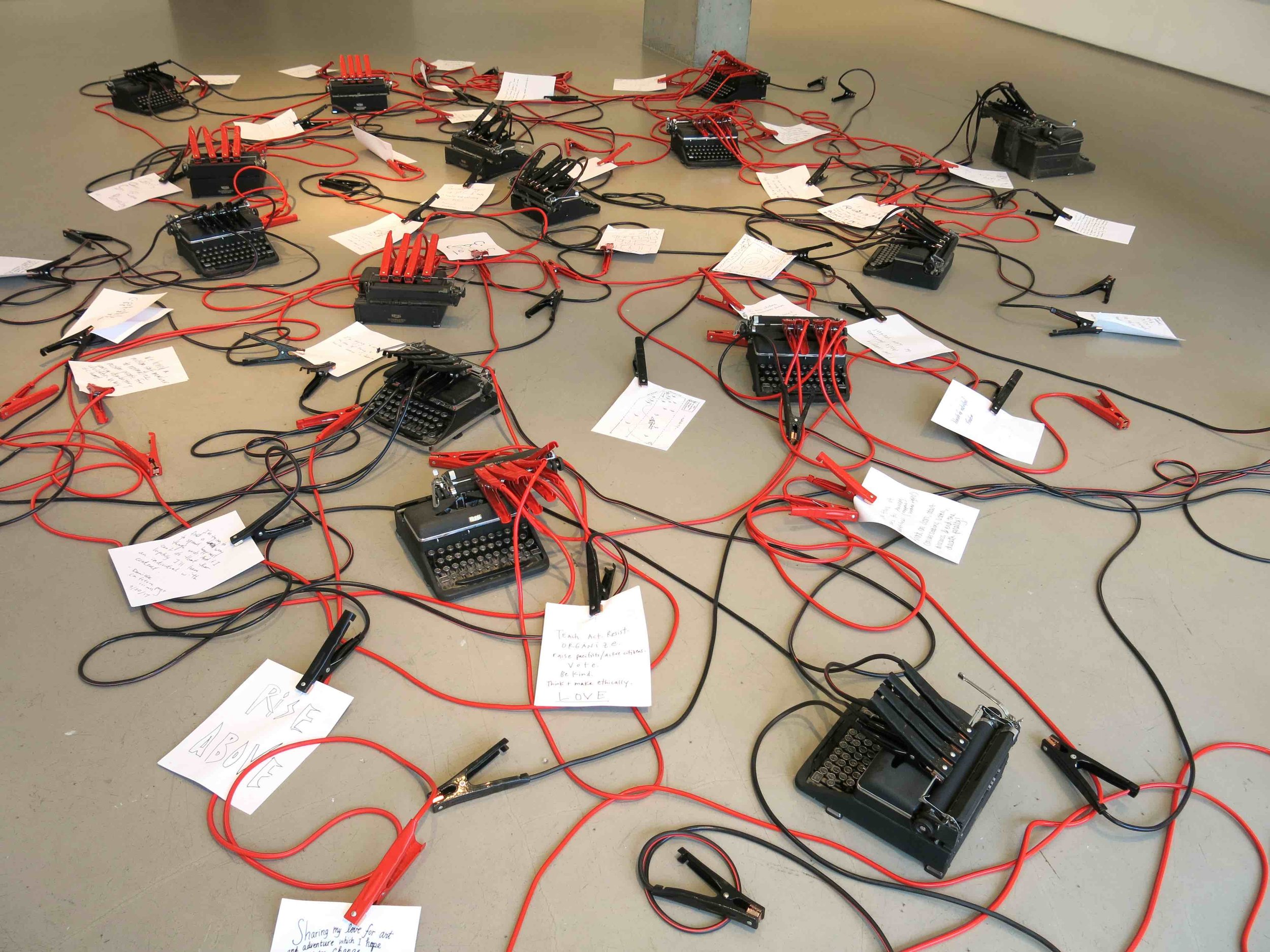

The focal point of the exhibition, Inside the Fire Circle, 2017, is a large, interactive floor installation consisting of jumper cables, obsolete typewriters, and blank sheets of paper on which visitors are encouraged to write, symbolizing a “jumpstart” to their own story or history. For Fatmi, “the installation is like a palimpsest of the modern age; the rhythmic flow between the paper and the cables seem as if they are sending signals back and forth, but at each stop the information is erased and the process begins again. This is a reflection of the tendency of history to repeat itself. The recent rise in nationalism across Europe, from Brexit in the UK, the rise of the National Front in France, Holland, Hungary, to the United States, and the state of affairs in Russia, Turkey and elsewhere, all reaffirm this fear.” The artist wants the cables to symbolically jumpstart people out of their apathy so they can learn from the past and become actively involved in writing a new and different story on the blank pages.

Fatmi’s wall sculpture Defense, 2016 is both an architectural object and readymade. In many parts of the world, these spiraled, pointed bars of metal function as security bars, installed to protect from intruders. It is aggressive and dangerous, but when placed within the context of an exhibition it takes on an added visual appeal, as a minimal sculpture that casts radiant shadows across the wall. The viewer must work around it in order to engage with the rest of the exhibition. Even in the distant past, these bars have been aesthetic and utilitarian, aggressive and attractive.

Another central work on view is a large photograph from The Blinding Light, 2013 - ongoing, a series of work inspired by a 15th century painting by Fra Angelico entitled The Healing of Deacon Justinian. The original painting depicts two saints, Cosmas and his brother Damian, grafting a black leg onto the deacon Justinian. Born in Syria, Cosmas and Damian were Arab by birth and later converted to Christianity. Fatmi’s photograph superimposes an image of the painting with an image from a contemporary surgical room. The transparency of images essentially fuses science and religion, present and past. Fatmi first saw this painting when he moved to Rome at age 17 to attend art school. He saw in himself a connection to being like that black leg, existing in a world that was not his own, in his case as a cultural transplant.

Calligraphy of Fire is a set of three black and white photographs. The images are enigmatic, as if offering a glimpse into a private ritual or an uncertain moment. For Fatmi, books and knowledge represent a means of survival, of opportunity, a path to independence, and a greater understanding of life. Calligraphy of Fire presents a set of situations, each of which links the idea of knowledge with light, and its absence, as darkness, a void. If the burning candle is symbolic of life, illumination, and knowledge, as it is throughout much of art history, in the left hand image the snuffed candle could suggest an impending opaqueness, the possible smudges as a form of censorship. On the right, the burning candle offers the possibility of light, yet if left unattended, the results will be destruction. In the center, the portrait of the artist suggests a movement from darkness into light, perhaps a path to self-awareness, growth, and even survival.

A small photo titled, Walking on the Light, shows a man at night, standing on the edge of circular light projection made by the artist titled, Technologia, which was a part of a 2012 exhibition in France. Fatmi took the photograph the night of the opening and it is only one of a few that exist as a few days later his installation was censored and removed from the exhibition. The light projection included verses from the Koran written out in beautiful calligraphy and combined into a swirling Marcel Duchamp inspired rotorelief. The controversy stemmed from the belief that the viewers would walk onto verses of the Koran, a sacred text, and as such considered destructive. But for Fatmi the work was about light and beauty, modernism and abstraction, and of course, no one could walk on those lines from the Koran as they were fleeting light, the shadow of the figure crossing onto the projection would in any case have blocked out the imagery under their feet.

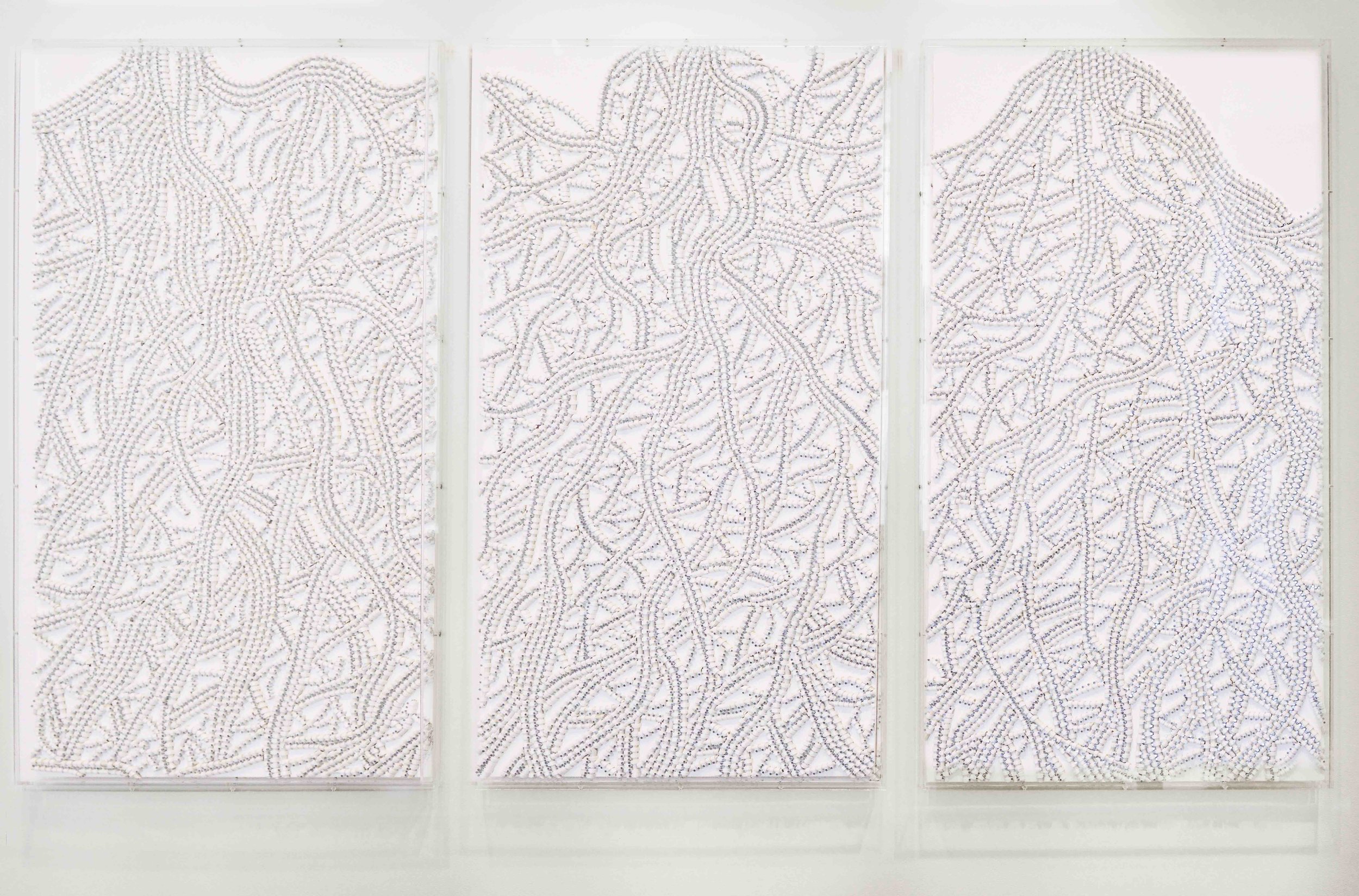

At first glance, Roots, a triptych made from white antenna cable seems to be simply an elegant work, but in fact the artist seeks to confront a more philosophical question: Just how deep can roots go? At a time when issues of identity and borders are increasingly in the news and being taken up by the extremes, the sculpture Roots, defends the idea of harmony and stability through its interlacing composition, a metaphor for the possibility of eventual union. The antenna cable serves as both core material and valuable archive in the sense that it is quickly becoming an obsolete material. As such, the work itself and this archive find themselves in a similar position and create a sort of dialogue. The archive creates the work and the work stores the archive.

The video, History is not mine, is a piece made partially in response to censorship. The black and white video depicts a man whose face remains concealed as he strikes a typewriter with two hammers. The only color comes from the typewriter’s ribbon, a brilliant red, the color of blood; a collision of the beauty of the written sentence and the violence and difficulty of its creation. The video plunges us into the role of witness and accomplice, as if we are almost a part of this story’s writing process. The simple and mundane gesture of striking the keys becomes crushing with the use of hammers. The weight that falls on the keys causes a deep, violent intonation. These effects, accentuated by the characteristic sound of a typewriter, also evoke the ticking of a clock or shots fired from a sub-machine gun. The artist urges the viewer to become aware of his or her stance vis-à-vis history. As evidenced by the title of the work, a feeling of hopelessness clearly emerges. The repetitive, angled shots overlooking the scene highlight a feeling of domination. By never showing the man’s face as he strikes the machine, Mounir Fatmi encourages the viewer to identify with his or her own experience. Everyone is a part of this story being written, the violence of the hammers, and the impossibility of writing something coherent with this method.

Alif, 2015 - ongoing, photographic piece showing a man’s forearm, grasping a slightly curved and elongated shape like a dagger, is a series of photographs begun in 2015 and is a work in progress that is to be developed on a set of photographs, videos, and installations. This shape known as the “Alif,” is the first letter of the Arabic alphabet. Alif is one of the six so-called “unrelated letters” or “isolated letters,” meaning that it is never attached to the letter that follows.